|

History  Sheep: Spinning & Weaving Sheep: Spinning & Weaving

These articles are taken from Sheep, Spinning & Weaving, by Katherine Reser, from the Douglas County Historical Society Journal, December, 1999. Our thanks to the Douglas County Museum for the use of these documents.

Sheep Shearing

Most people favored shearing their sheep in March or early April. However, one family thought Decoration Day was the best time of all. More Choosing and Cleaning Fleece

In the spring, (about sheep shearing time?) when it was time to quit wearing the heavy woolen winter clothes, our lady probably took inventory of what had to be replaced or added to the family wardrobe. We don't know if she wrote it down or kept it in her head. More Carding and Other Ways

There were different methods of aligning or combing the fiber. Some of these were carding, flecking, or combing. Some spun without doing any of these. More Natural Dyeing

The use of plants, bark, leaves, seeds, blossoms, lichens and wood to dye natural fibers has been going on for centuries all over the world. More | Sheep Shearing A settler's family could know a great deal of hardship if crops failed or their animals did not reproduce or if their food supply failed. Most of the families planted crops, harvested, butchered etc. by the increasing or decreasing of the moon. For example: A lamb or hog was never butchered during the full of the moon. The meat would puff up or the bacon would not lay flat in the skillet! One did not shear nor wash wool when the moon was decreasing. The wool would never stop shrinking, or so it was thought. In those times people left little to chance. If they were careless they might very well go hungry or cold before the next year's crops came in. Most people favored shearing their sheep in March or early April. However, one family thought Decoration Day was the best time of all. Sometimes, it may have depended on the breed. The Fin Sheep will shed off parts of their fleece but not all. The patches left behind still have to be sheared. They can, by shedding, make an ordinary pasture look like a cotton patch ready to be picked! These and similar breeds were probably sheared earlier. When the proper time arrived the sheep were penned up the night before, or in a pasture close to the barn, if the pens were muddy. The wise person did not pen them up in the Chicken house - if there was to be peace in the family. When one considers how much depended on getting a fleece, carded and spun quickly into yarn - everyone was responsible not to let the sheep get any more soiled than necessary. Most shearing was done on a dry day. Hooves were trimmed and animals doctored as needed. Hand powered clippers were used in Douglas County (MO) until the 1930's. There was a pump-foot clipper. It was treadled like a treadle sewing machine. This treadling provided the power to move the clipper teeth which cut the fleece off. The coming of electricity was a great relief to everyone. There was no small amount of skill required to use hand held clippers, hold a sheep down, take long even strokes and not cut gashes in the sheep or have too many short cuts in the fleece. Even with electric clippers it's still worth one's time to watch a skilled sheep shearer work. The term, 'short cut', happens when the clippers do not clip close enough to the sheep. A return pass with the clippers was done and the 'short cuts' ended up in the fleece. Spinners are not happy with these! The sheep was flipped over on its back, fleece cut off belly, chest, face, and then up each side toward the back. The sheep was stood up and the fleece sheared off the back, all in one piece. It was then rolled up inside out and tied with a string if the family intended to keep it. If the family had more fleeces than they needed, they could sell them out individually. Later on there were wool buying companies. If they were selling commercially there was a platform with a framework to hold a seven or eight foot wool sack. The fleeces were tossing into this sack. A child would trample the fleeces down until the sack was full. Everyone, no doubt, heaved a big sigh of relief when the last sheep was sheared! Glad that it would be another year before this had to be done again. Years later the Douglas County Feed Mill bought extra fleeces. The Douglas County Herald, in 1887, had an ad for sheep hides. The Old Mill, as many will recall, was located where Casey's is today. Some families considered the money made from the sale of the wool to be their profit from raising the sheep.

Choosing and Cleaning Fleece In the spring, (about sheep shearing time?) when it was time to quit wearing the heavy woolen winter clothes, Our lady probably took inventory of what had to be replaced or added to the family wardrobe. We don't know if she wrote it down or kept it in her head. This list, kept in mind, helped her sort through the fleeces and pick out what and how many she needed for the next season. It would also determine how the fleeces were scoured or washed. For example, if a waterproof garment was needed the lanolin would be left in. (Now do keep in mind that these next activities were done at the correct times!) Can you picture a laughing mother and her children with a bag of wool, bright sunshine bouncing off the ripples in a spring branch? Oh Yes! They will have fun - water is to be enjoyed - and watched closely for snakes. Mother, may have sat on that big rock that was half buried in the san d and gravel of the spring branch. She would have tucked her skirt up under her to keep them dry. No one knows how many times she wiggled her bare toes and laughed at the minnows nibbling. After the children had splashed a while and the water cleared then the reason they were here had to be dealt with. A child might have stood on each side of her. One handed her a small amount of fleece which she dipped into the water until the barnyard was left behind. This was handed to the next child who gently squeezed the water out and placed it into a tub - to be carried back to the house. The fun of washing fleece in the spring branch is just as much fun today as it was in yesteryear! This fleece, which had been washed in cold water, would be used for gloves or mittens or a heavy outer sweater that would shed the spring or fall rains. The lanolin was left in. Different spinners had different ideas about using their fleece. Some preferred to "Spin in the grease." This meant taking a sheared fleece, as it came from the sheep's back, and spinning it into yarn without washing it first. This was usually a very clean fleece. After the yarn was spun, then it was washed. "Spinning in the grease" did leave a residue on the orifice and flyer of the spinning wheel, which had to be cleaned. Most fleeces were scoured or washed in hot water (dishwater hot). They always remembered 2 rules: The wash water and rinse water must always be the same temperature. If not, shrinkage would occur. Number two, after fleece was in the soapy wash water it was not stirred or agitated, otherwise they could end up with poor quality felt or a big matted mess. After a portion of fleece had soaked a few minutes in soapy water it was carefully lifted out, pressed gently and put into the next container of water. The next tow waters were clear. Lye soap is still used by some to scour fleece. The P.H. balance is correct. Many buckets of water were carried and emptied into the old iron kettle, which was heated with a fire built under it. This chore probably fell to the children. If the fleece was to be carded, it was picked or teased before it was washed. The locks were plucked off and the ends opened to permit easier cleaning. The process would take 2 experienced people 4 hours or several people 1 hour. They could blend the fleece better this way, especially a colored fleece. Some parts of a fleece are coarser than others. These could be set aside at this point.

Carding and Other Ways There were different methods of aligning or combing the fiber. Some of these were carding, flecking, or combing. Some spun without doing any of these. If one chose to spin without doing anything beforehand, then the fleece was washed in large pieces. They would simply pluck off a lock at a time and spin each one into yarn. Flecking was done by using a coarse comb (like a dog comb.) Taking one lock at a time, grasping firmly in the center and combing first one end and then the other. As each one was combed it was laid aside into a basket to be spun to yarn later. English and Viking combs may have been used. These look like wooden blacks with rows of long spike nails sticking up. One was fastened to a table and locks of fleece were pushed down into the nails like teeth. When filled the other comb was struck at the protruding ends of the fleece in a long swinging motion this was done until all the fleece was removed from the first comb. The fleece was then pulled through a "driz." This was a flat disk with a hole in it. As the fibers were pulled through he "driz" a long string about 4-6 foot long was formed. This was wound around the fingers until the last 6-8 inches were reached. These last few inches were tucked into the center leaving a tail sticking out. Some of these were known as "birds nests." Children may have been handy at making these. If a fleece needed to be blended it was usually carded. It was picked before scouring, then picked again before carding. Carders were wooden paddles with numerous wire teeth set into a leather face on each paddle. When one was loaded with fleece the other carder brushed down and against and straighted out the fibers. It depended on the fleece as well as the project whether they would comb 2 or more times. The better the job of carding the smoother the fibers could be spun. When the fibers were straight they were taken off the carders and the edges were curled under. This was called a rolag. They looked like fat, sleeping puppies when laid carefully in rows in a basket. One other method was to roll the fibers off so that the fibers were straight instead of curled under. This was known as the worsted method. They were ready to be spun into yarn. After the fleece was scoured according to the purpose intended, it may have been dried on a wooden rack that was lined with a cloth. The cloth was to keep the wood from discoloring the fleece. I there were no puppies, cats or chickens looking for a bed in the fresh washed fleece then the cloth may have been spread over the woodpile. The uneven spaced made perfect drying pouches. It was recommended to dry fleece in the shade. Fleeces kept better and were easier to spin if they were washed soon after shearing. Moths were an ongoing problem. Cedar chips and certain herb combinations were used to keep moths at bay. Our lady needed a great deal of knowledge to do all these processes. This was handed down from one generation to the next. Children were often given the job of carding wool or seeding (removing seeds) from cotton. Some of our senior citizens can remember carding wool for their grandmothers.

Natural Dyeing The use of plants, bark, leaves, seeds, blossoms, lichens and wood to dye natural fibers has been going on for centuries all over the world. It was perfectly natural for the pioneers to carry a supply of those that were not already growing wild here in Douglas County (MO). Herbs used for medicine were also brought along. Often the same herb was used for both purposes. The woodland here was similar to what many people had left behind. However, some plants needed protection and cultivation. Madder roots when crushed gave a beautiful tomato red dye. Wild-yellow marigolds were cherished and of course indigo. The beautiful green orchard gave peach tree leaves. These were picked just before frost and placed to dry in an airy place to prevent mildew. A golden yellow could be looked forward to.  The very garden provided dye plants as well. Red cabbage for a tan; onion skins an orange; green tomato vines, gathered before frost and placed in the dye pot, simmered; blackberry vine leaves gave tan. The pasture had many weeds such as goldenrod (photo at left) to give us gold. The very garden provided dye plants as well. Red cabbage for a tan; onion skins an orange; green tomato vines, gathered before frost and placed in the dye pot, simmered; blackberry vine leaves gave tan. The pasture had many weeds such as goldenrod (photo at left) to give us gold.

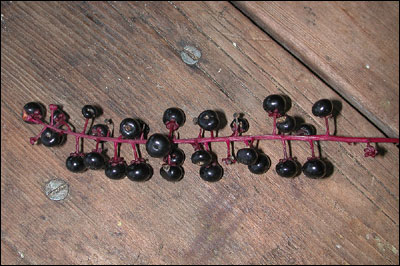

The woods provided so many colors. One would think as abundant as dye plants are in Douglas County (MO) that hardly anyone would go dashing off to the store to buy a package of commercial dye. The know-how, availability of materials, and time involved just about guarantees that most of us will take the easy way out and buy a box of dye, since we do have a choice. Our lady pioneer had no such choice. She probably followed her mother or grandmother each time dye plants were gathered. By the time she was school age she probably knew the names of almost all of them. Her little hands were welcome. It took a number of dye plants to dye the fiber.  Different dye plants had to be gathered at different times of the year. Poke berries (photo at right) were probably used as soon as they were ripe. Remember they did not have canning jars 150 years ago, much less home freezers. Poke berries make beautiful red dye, especially with vinegar as a mordant. It does tend to fade. The colors or red are so glorious that even faded the are still worthwhile. A day of natural dyeing is messy even in the year of 1999. We can be reasonably sure that in the early 1800's it was not that much different. Some dye plants were soaked in water for 24 hours of longer, then boiled, stained, and returned to the dye pot and simmered. Different dye plants had to be gathered at different times of the year. Poke berries (photo at right) were probably used as soon as they were ripe. Remember they did not have canning jars 150 years ago, much less home freezers. Poke berries make beautiful red dye, especially with vinegar as a mordant. It does tend to fade. The colors or red are so glorious that even faded the are still worthwhile. A day of natural dyeing is messy even in the year of 1999. We can be reasonably sure that in the early 1800's it was not that much different. Some dye plants were soaked in water for 24 hours of longer, then boiled, stained, and returned to the dye pot and simmered.

Dyeing an entire unspun fleece could be challenging. One could dye the yarn after it was spun or wait until the garment was finished. Smaller amounts of fleece could be dyed to provide contrasting stripes. Cotton and linen or combinations thereof were also dyed. The availability of water especially during drouth years may have also influenced the times of drying. Why was color so important in clothes? The soft natural whites and creams of wool and cotton are pretty by themselves. Were they artists? Was it spiritual? Some cultures revere certain colors as part of their religious belief. Here in Douglas County there was a far more practical side to this. We have to remember in those days all laundry was done by hand, on a washboard and with lye soap. Some folks took their laundry to the creek and rubbed their clothes on the rocks to get them clean and then hung them on the bushes to dry. Bathing and changing clothes took place about one per week or longer if freezing weather was upon them. The tradition of a bath on Saturday may have gotten its start from this. Light colored clothes were saved for wearing to church or whenever an occasion called for "dressing up." Upon arriving home the entire family changed back into their every day clothes. White clothes were kept white by always washing them by themselves and boiling in a kettle to remove stains. Almost every family had a huge cast iron kettle sitting in the back yard where it could be filled with water and a fire built underneath it.  Some of us have heard the term,"he was dressed up. He had on a boiled white shirt." People's character was often judged by how white their clothes were, often under those circumstances the soft browns and tans and gold from black walnut (photo at left), hickory, elm, butternut were more than welcome. The list of dye plants is almost endless. Clothing, dyed with these, kept the family from looking too dirt stained before the next wash day. Some of us have heard the term,"he was dressed up. He had on a boiled white shirt." People's character was often judged by how white their clothes were, often under those circumstances the soft browns and tans and gold from black walnut (photo at left), hickory, elm, butternut were more than welcome. The list of dye plants is almost endless. Clothing, dyed with these, kept the family from looking too dirt stained before the next wash day.

Mordents were used to help set the color, change it, darken or brighten. Salt, Vinegar, cream of tartar, tin, chrome, copper and some spices. This list is lengthy also. Mordents and water solutions were made up, fiber or garment soaked in it, then placed in the dye bath. One dye bath could have several shades and colors produced from it, depending on the mordant. Why would anyone want to do natural dyeing in 1999? It's a journey of discovery a touching of the past, fun! The colors are more subdued and have a quality different than commercial dye. They do face more easily. Sometimes it's difficult to obtain information on how and what material to gather as well as the process for dying the fibers. Persons interested may contact Country Heritage Spinning and Weaving Guild, Box 1505, Ava, Mo. They usually have a hands on workshop every year and visitors are welcome.

|